What, to him, was the American flag?

By David Harmer

Born and raised in the United States, he was American through and through. He’d been a newspaper delivery boy, a Boy Scout, in Junior ROTC. Now the nation—his nation—was at war. So he volunteered for military service—and was rejected. The government deemed him ineligible for one reason: his ancestry.

His parents loved the American West, with its wide-open spaces and egalitarian ethos. They’d settled in Gallup, New Mexico, where they ran a 24-hour diner. They spoke English both in public and at home. They never spoke of the old country; they considered themselves nothing but American.

But they had immigrated, years earlier, from Japan; and now Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor. So the U.S. Armed Forces classified their son, Hiroshi Miyamura (“Hershey” to his friends), as 4C: an enemy alien.

Put yourself in young Hiroshi’s shoes. How would you feel about the American flag?

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s infamous Executive Order 9066 forced tens of thousands of Americans of Japanese descent out of their homes and into internment camps. New Mexico was far enough from the Pacific Coast that the Miyamura family wasn’t affected directly. But thousands of Japanese Americans were shipped through Gallup by train en route to inland internment camps. Hiroshi saw some of them.

Later in the war, the exclusionary policy changed; Hiroshi was allowed to join the Army. He was assigned to a segregated unit: the 442nd Infantry Regimental Combat Team, composed almost entirely of Japanese Americans, many of whom had families incarcerated in the camps. The orders establishing the unit specified that “officers of field grade and captains . . . will be white American citizens.”

Hiroshi reached Europe just as the war there was ending. After returning home, approaching the end of his enlistment, he married Terry Tsuchimori, whose family had been held in a camp in Arizona.

Put yourself in the shoes of those newlyweds, one a veteran of a segregated army, one the daughter of a family incarcerated for their ethnicity. What would the American flag mean to you?

Two years later, the Northern Korean People’s Army invaded South Korea, and Hiroshi was called up from the reserves for active duty.

“When we landed in North Korea, it was winter,” he recalled. “I’d never been so cold in my life. We didn’t have proper clothing. It was miserable.”

Fast forward to the night of April 24, 1951. An overwhelming force attacked, threatening to overrun Company H’s position. To defend his men, Corporal Hiroshi Miyamura jumped out of his shelter into hand-to-hand combat, killing ten with his bayonet. The charge repelled, he administered first aid and directed the evacuation of the wounded. Assaulted again, he fired until his ammunition was gone, then ordered his squad to withdraw to safety while he stayed behind. He bayoneted his way to another gun emplacement and assisted there, killing another fifty. Severely wounded, he stayed at his post until his position was overrun. Fighting his way toward the U.S. fallback position, he caught shrapnel from a grenade and lost consciousness.

Reported as missing in action, he awoke as a prisoner of war. A brutal forced march to a prison camp was followed by 27 harrowing months of malnutrition and torture. The communists refused to release the names of the prisoners they’d taken, so for months his fate was unknown. Emaciated, he was finally repatriated.

How did he feel about the American flag?

Tears streamed down his face when he saw it. Decades later, when he recounted the experience to a rapt audience of K-12 teachers at Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge, tears streamed down his face again.

“When I saw that flag, the star-spangled banner, waving in the breeze,” he began—and then he choked up.

“I’ve learned what it represents,” he continued. “This is the most wonderful country in the world.”

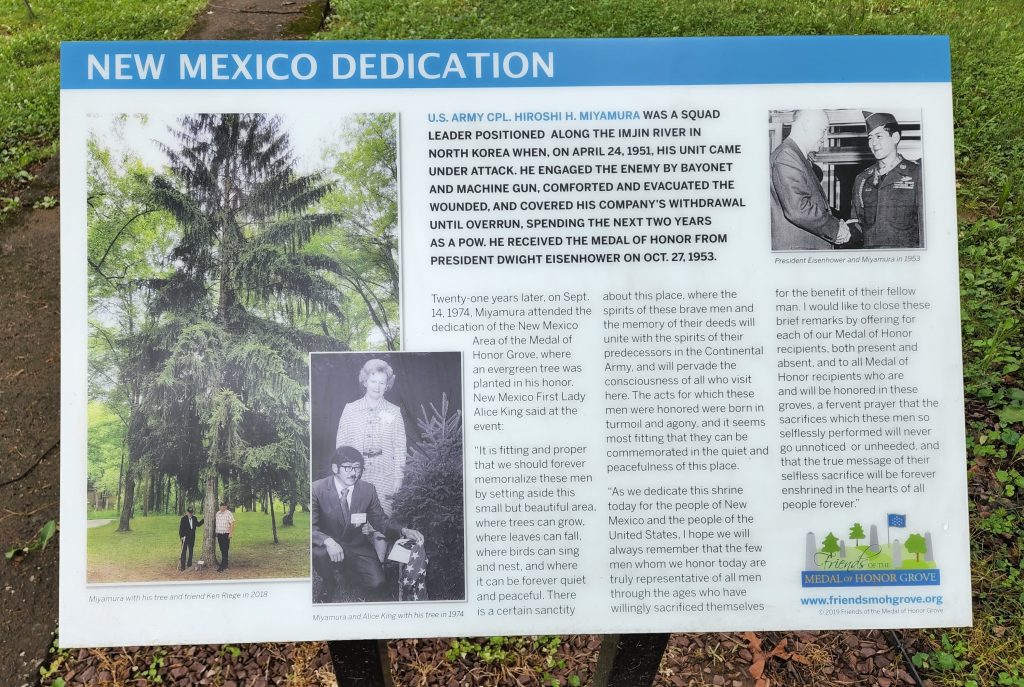

In 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower, founding chairman of Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge, presented to Corporal Miyamura the Congressional Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for valor in action against an enemy force.

In 1974, Miyamura attended the dedication of the New Mexico Area of the Medal of Honor Grove, hosted on our Valley Forge campus.

If you visit the Medal of Honor Grove today, you’ll find, near the New Mexico obelisk, a handsome interpretive plaque that includes a picture of Miyamura by a small tree planted in his honor on that occasion in 1974—and a picture of him by the same tree, fully grown, when he returned 45 years later.

On this Flag Day, we honor him—and venture the hope that his fellow citizens will perceive the flag, and the Republic for which it stands, as he does.

Donate Today

Supporting America’s first principles of freedom is essential to ensure future generations understand and cherish the blessings of liberty. With your donation, we will reach even more young people with the truth of America’s unique past, its promising future, and the liberty for which it stands. Help us prepare the next generation of leaders.