Happy birthday, Bill of Rights!

By David Harmer

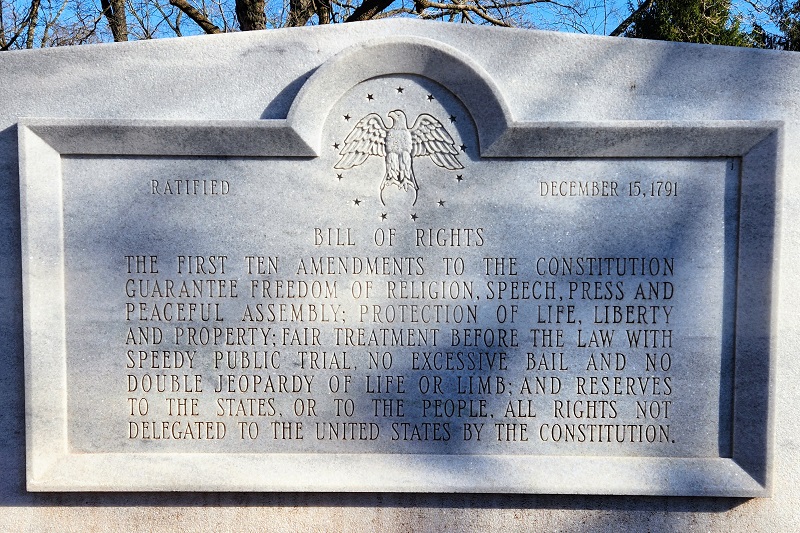

On this day in 1791, the Bill of Rights was added to the Constitution. How well do you know the story? Take this quiz to find out!

- Why did the Constitution originally not include a bill of rights?

- Why was the Bill of Rights added?

- What procedures governed adoption of the Bill of Rights?

- The Bill of Rights was readily accepted. True or false?

- What’s the best way to teach young people about the Bill of Rights?

ANSWERS

1. Why did the Constitution originally not include a bill of rights?

When Virginia delegate George Mason proposed one, the Constitutional Convention rejected it. Delegates voted by state; every state rejected the proposal but Massachusetts, which abstained. As a practical matter, Mason’s proposal arose too late in the process (September 12, 1787) to gain traction. After enduring a sweltering summer with the doors and windows closed, the delegates were on the verge of achieving consensus on the framework of the new government. They were in no mood to prolong the proceedings.

Their aversion to a bill of rights reflected more than eagerness to complete their work. Most delegates considered a bill of rights at best unnecessary, at worst dangerous, and in any case futile.

- Unnecessary: The people would retain all rights not expressly relinquished; the government would gain only those powers expressly granted. The Constitution granted no power to abridge rights.

- Dangerous: The expression of certain rights would imply the exclusion of all others. Declaring exceptions to powers that hadn’t been granted would imply the existence of those very powers, contrary to the framers’ intent.

- Futile: James Madison expressed skepticism that a person or government determined to usurp power could be restrained by “parchment barriers.”

2. Why was the Bill of Rights added?

A bill of rights became necessary to ensure ratification of the Constitution, to unite all 13 states, and to fully incorporate Anti-Federalists into the body politic.

- Ratification: For the Constitution to take effect, Article VII required ratification by the conventions of nine states. Within four months, it was easily ratified by five. But Anti-Federalists organized and polemicized, putting ratification at risk elsewhere—especially Massachusetts, where the Federalists, in danger of losing, negotiated a compromise: key Anti-Federalists would vote to ratify but would recommend amendments including a bill of rights; Federalists would support the amendments. Even with Governor Hancock introducing the compromise and Samuel Adams supporting it, the vote was close: 187-168. Most later states followed the Massachusetts model, ratifying (sometimes narrowly: New Hampshire, 57-47; Virginia, 89-79; New York, 30-27) but recommending amendments.

- Union: When President Washington took office, North Carolina had voted against ratification and Rhode Island hadn’t voted at all. Among the principal reasons for their self-exclusion from the union was its lack of a bill of rights.

- Inclusion: In the First Congress, Madison championed a bill of rights not only to keep the promises that secured ratification, and to entice the holdout states to join the union, but to cultivate support for the Constitution among those who had opposed it. Many Americans feared that the new national government would encroach on state powers and individual rights. A bill of rights would allay their fears. Madison aimed to induce them to participate fully in the new government and develop loyalty to the Constitution.

3. What procedures governed adoption of the Bill of Rights?

Article V: “The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose Amendments to this Constitution . . . which . . . shall be valid to all Intents and Purposes, as Part of this Constitution, when ratified by the Legislatures of three fourths of the several States.”

Via joint resolution on September 25, 1789, the First Congress sent to the states 12 amendments. Over the next two years, most states ratified most of them. On December 15, 1791, Virginia’s legislature became the 11th to ratify the 10 amendments known as the Bill of Rights, thus adding them to the Constitution. By then, North Carolina, Rhode Island, and Vermont had ratified the Constitution, so 11 of 14 states were required to reach the three-fourths threshold.

4. The Bill of Rights was readily accepted. True or false?

False! Lynne Cheney explains:

Madison . . . reviewed the more than two hundred amendments that had been proposed in state ratifying conventions and then neatly set aside all of those that would weaken the central government. Amendments having to do with individual rights remained, and he incorporated them into proposals for the Congress. . . .

The heated battle to get the amendments through the Congress went on for months. Wrote Madison, “The difficulty of uniting the minds of men accustomed to think, and act differently can only be conceived by those who have witnessed it.” Madison kept at it. . . . [He] was not only deeply knowledgeable and politically creative, he also had persistence. [1]

Prodigious though they were, Madison’s preparation, persuasion, and persistence weren’t enough; he had to summon higher authority. Ron Chernow writes:

Encountering heavy resistance in the new Congress, Madison asked Washington for a show of support for the amendments and elicited from him an all-important letter in late May 1789. While some of the proposed amendments, Washington wrote, “are importantly necessary,” others were needed “to quiet the fears of some respectable characters and well meaning men. Upon the whole, therefore . . . they have my wishes for a favorable reception in both houses.” This letter helped to break the logjam in Congress. . . . Washington’s involvement was all the more notable in that he normally hesitated to meddle in the legislative process. [2]

5. What’s the best way to teach young people about the Bill of Rights?

Send them (or their teachers) to Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge! Our superb staff has prepared an ambitious calendar for the coming year chock-full of inspiring programs on the history and continuing importance of the charters of American freedom—emphatically including the Bill of Rights.

________

[1] Lynne Cheney, The Virginia Dynasty: Four Presidents and the Creation of the American Nation, pp. 108-110; citation omitted.

[2] Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life, pp. 607.

Donate Today

Supporting America’s first principles of freedom is essential to ensure future generations understand and cherish the blessings of liberty. With your donation, we will reach even more young people with the truth of America’s unique past, its promising future, and the liberty for which it stands. Help us prepare the next generation of leaders.