“I have a dream”

By David Harmer

Born on this date in 1929 was Martin Luther King, Jr., who would become the foremost leader of America’s civil rights movement. King graduated from Morehouse College; received a divinity degree from Crozer Theological Seminary in Upland, Pennsylvania; and earned his doctorate in systematic theology from Boston University. Returning to the South, he served as pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery and co-pastor (with his father) of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta.

His commitment to civil rights grew from his faith. His oratory was suffused with biblical allusions. So was his life. He practiced what he preached.

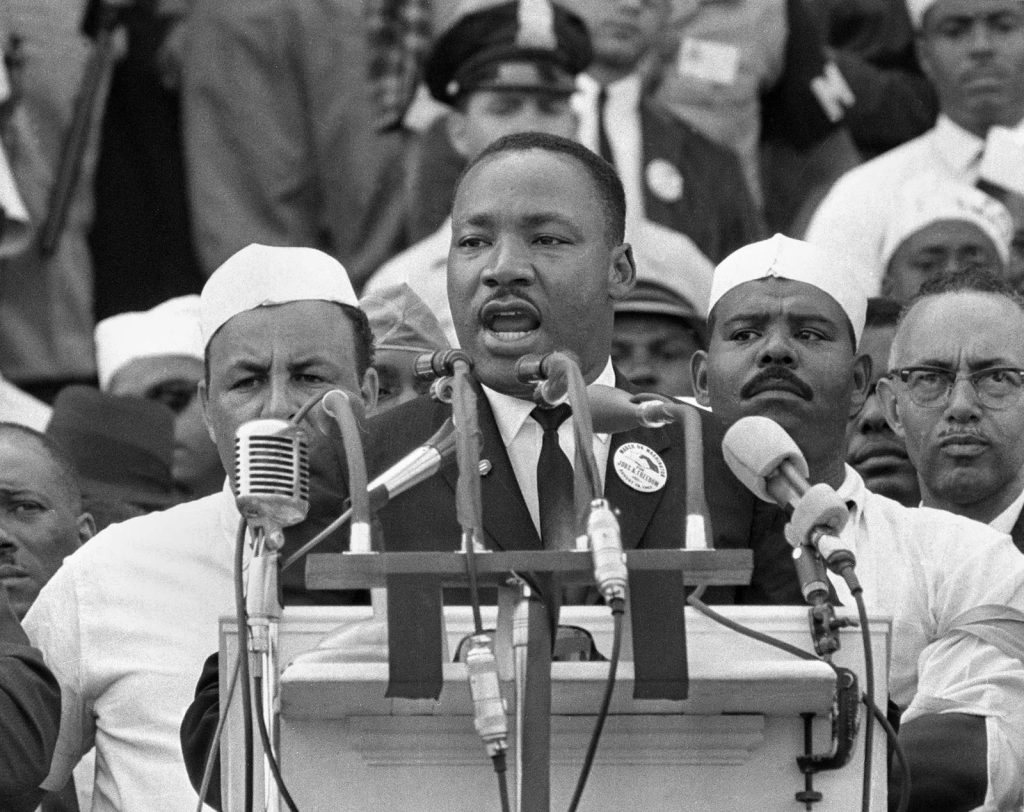

Martyred at age 39, he is justifiably famed for his presidency of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and his receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize. But Dr. King is best known for “I have a dream,” the speech he delivered on August 28, 1963, as the culmination of the March on Washington.

A quarter-million people had gathered on the National Mall to protest state-sanctioned racial discrimination, which King correctly identified as an affront to America’s founding ideals. Following the Civil War, the nation had experienced, as President Lincoln had resolved, “a new birth of freedom”: the 13th Amendment prohibited slavery; the 14th extended equal protection of the laws to all; the 15th affirmed the right to vote regardless of race, color, or previous servitude. But the promise of Reconstruction faded as the states of the former Confederacy imposed a thicket of legal impediments to racial equality and turned a blind eye to race-based terrorism. The Union may have won the War, but the Confederacy, in many respects, won the ensuing peace—if we can call it that.

Thus it was that Dr. King, speaking from the Lincoln Memorial, began:

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination.

King called for “the Negro [to be] granted his citizenship rights.” He stated his case plainly, grounding it in the text of America’s founding documents:

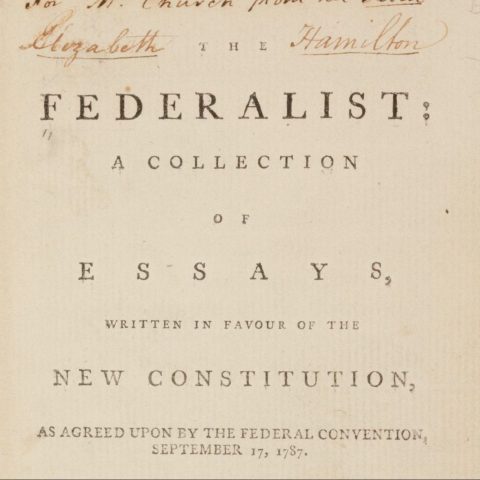

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men—yes, black men as well as white men—would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

Even as he acknowledged “the dark and desolate valley of segregation” and “the unspeakable horrors of police brutality” in “this sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent,” King abjured violence:

In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.

We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence.

He acknowledged that many in his audience had “come here out of great trials and tribulations,” some “fresh from narrow jail cells,” others from “areas where your quest for freedom left you battered.” Even so, he said:

I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. . . .

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. . . . I have a dream that . . . one day right down in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. . . .

This is our hope.

Here at Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge, it is our hope as well.

Donate Today

Supporting America’s first principles of freedom is essential to ensure future generations understand and cherish the blessings of liberty. With your donation, we will reach even more young people with the truth of America’s unique past, its promising future, and the liberty for which it stands. Help us prepare the next generation of leaders.