Prayer at Valley Forge

By David Harmer

On this day in 1777, General Washington led the soldiers of the Continental Army into Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. Here, 20 miles northwest of Philadelphia, they established the winter encampment that became the crucible of the American Revolution.

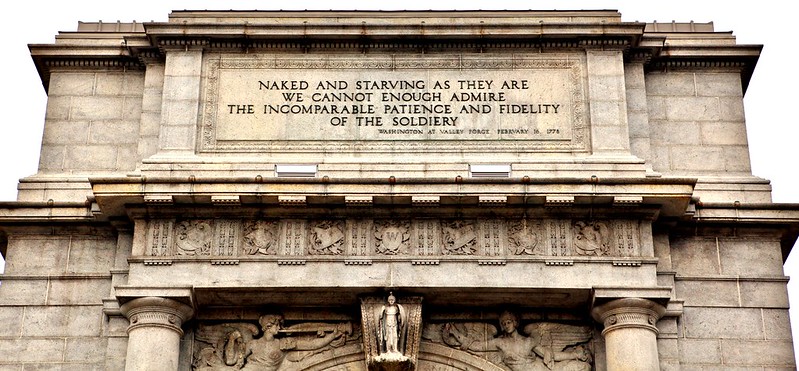

Some idea of their suffering can be gleaned from Washington’s words, written less than two months later and now engraved in the National Memorial Arch:

Naked and starving as they are

We cannot enough admire

The incomparable patience and fidelity

Of the soldiery.

Naked? Alas, yes. Thousands of his men lacked boots, coats, gloves, or blankets. Shocked visitors wrote that many soldiers wore shirts and trousers so tattered that their skin was exposed, and for shoes wore only rags.

Starving? Here are Washington’s words in context, in a letter he wrote to New York Governor George Clinton (punctuation modernized):

It is a subject that occasions me more distress than I have felt since the commencement of the war . . . I mean the present dreadful situation of the army for want of provisions. . . For some days past there has been little less than a famine in camp. A part of the army has been a week without any kind of flesh & the rest three or four days. Naked and starving as they are, we cannot eno⟨ugh⟩ admire the incomparable patience and fidelity of the soldiery, that they have not been, ere this, excited by their sufferings to a general mutiny and dispersion.

The situation was even worse than Washington let on. With the British army so near, and both sides employing spies, any letter risked interception—so he couldn’t disclose the army’s true condition. Otherwise General Howe, learning how destitute, hungry, and weakened Washington’s men really were, would surely attack, likely destroying the entire force.

In those dire circumstances, Isaac Potts, owner of the modest stone home serving as Washington’s headquarters, reportedly noticed Washington heading into the woods alone and, following undetected, found him kneeling in prayer in the snow. Historians doubt that account, as it emerged only secondhand, decades later. But that Washington prayed at Valley Forge is plausible, indeed likely. Thomas Fleming writes:

This historian has long been one of the strongest skeptics of the prayer in the snow at Valley Forge. But recent research has revealed a surprising depth to Washington’s faith in the divinity he called “Providence.” . . . With his army dissolving into mutiny, with Generals Mifflin and Gates doing their utmost to ruin him, and with Lafayette about to invade Canada with unforeseeable but potentially ruinous consequences to Washington’s prestige, could this man, alone in the wintry woods, have sunk to his knees (or one knee, as some artists imagine)? Perhaps. . . These were thoughts that might bring the strongest man to his knees. [1]

Michael and Jana Novak go further:

The “knowledge” that Washington slipped off for private prayer had currency. If true, it would not have been out of character with the piety of his private letters. If true, it would have put Washington’s appeals to his officers and soldiers for public and private prayer on the solid foundation of his own example. . . The Rev. Stone’s report of some knowledge about Washington’s recourse to private prayer during the war (and not only during the war) is backed up by many others, including some in Washington’s own family. [2]

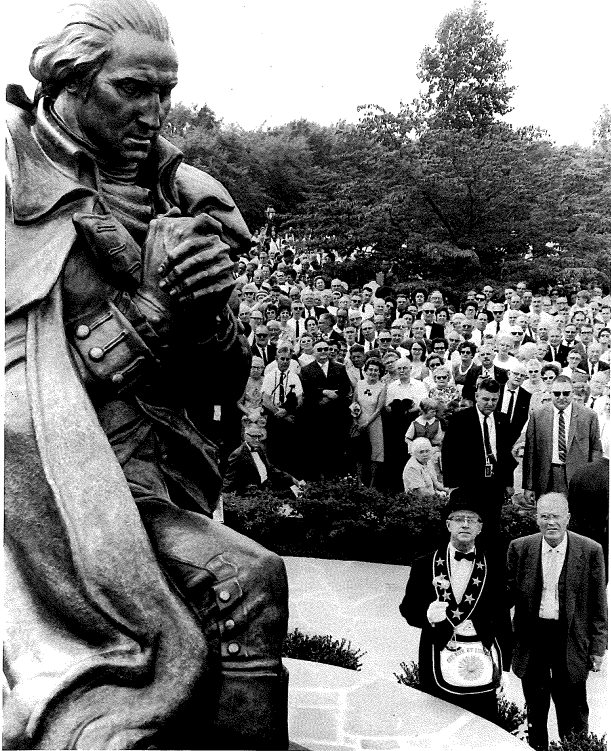

Thus, we at Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge are confident not only in the symbolic significance but the historicity of the focal point of our campus, found just east of my office, on the brow of an expansive hillside overlooking our Medal of Honor Grove: a heroic statue of Washington kneeling in prayer in Valley Forge. This magnificent nine-foot bronze, by sculptor Donald DeLue, was a gift to us from the Pennsylvania Freemasons in honor of their brother Mason, General Washington. More than 20,000 Masons and their families witnessed its September 1967 dedication. That assembly ranks among the largest gatherings of Masons in the history of the Grand Lodge and among the largest crowds ever to witness the unveiling and dedication of any statue in the United States.

In the 55 years since its dedication, portions of the statue had grown discolored due to age, wear, and runoff from acid rain. I’m pleased to report that from August through October of this year, under the aegis of the Masonic Library and Museum of Pennsylvania, the statue was fully restored to its original splendor. Crews cleaned it thoroughly, reintegrating color where necessary, applying a wax coating to protect the bronze surface, and clearing small weepholes so rainwater could drain properly. They disassembled the entire base, cleaned the original mortar off the stones and concrete core, and reassembled the base in its original configuration, using new mortar.

On this, the 245th anniversary of Washington’s arrival here, the statue commemorating his reliance on Providence stands strong. May it remind generations to come of the faith of all who bore the ordeals and secured the ultimate triumph of the American Revolution.

___

[1] Thomas Fleming, Washington’s Secret War: The Hidden History of Valley Forge, pp. 190-191.

[2] Michael Novak and Jana Novak, Washington’s God: Religion, Liberty, and the Father of Our Country, pp. 222.

Donate Today

Supporting America’s first principles of freedom is essential to ensure future generations understand and cherish the blessings of liberty. With your donation, we will reach even more young people with the truth of America’s unique past, its promising future, and the liberty for which it stands. Help us prepare the next generation of leaders.