Black History Month: Slavery and the Founding

By David Harmer

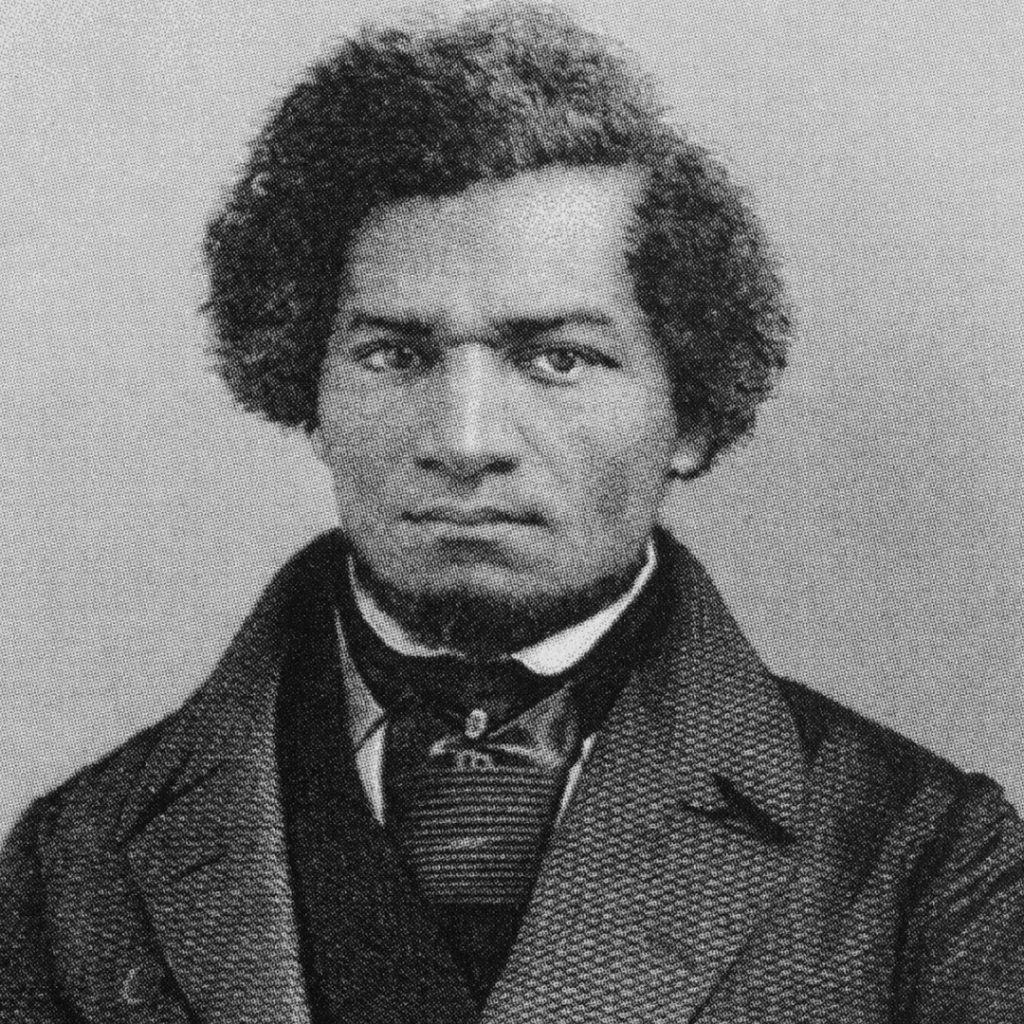

Encompassing the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, the first Negro History Week was observed in 1926. Fifty years later, in connection with the nation’s bicentennial, the annual observance was expanded to a month. In his message marking the occasion, President Gerald Ford declared:

Freedom and the recognition of individual rights are what our Revolution was all about. They were ideals that inspired our fight for Independence: ideals that we have been striving to live up to ever since. Yet it took many years before these ideals became a reality for black citizens.

The last quarter-century has finally witnessed significant strides in the full integration of black people into every area of national life. In celebrating Black History Month, we can take satisfaction from this recent progress in the realization of the ideals envisioned by our Founding Fathers. But, even more than this, we can seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.

Nearly half a century later, President Ford’s message resurrects uncomfortable realities. “It took many years,” he acknowledges, before the founding ideals of individual rights and freedom “became a reality for black citizens.” Only in the preceding quarter century had the nation “finally witnessed significant strides in the full integration of black people into every area of national life.”

Here at Freedoms Foundation, we’re proud that our founding father, President Eisenhower, took one of the largest of those strides when he issued the executive order directing troops under federal authority to ensure the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. In observance of Black History Month, we regretfully acknowledge the fact and legacy of slavery, America’s original sin; but we also recognize America’s repentance of that sin and her continuing progress toward realization of her founding ideals.

America at her founding was hardly unique in permitting slavery. The immoral practice was global, endemic on every inhabited continent, found among aboriginal inhabitants as well as colonizers and traders. Individuals of various races and religions enslaved others, and individuals of various races and religions were themselves enslaved. On portions of the African continent, it’s estimated that a third of the population was enslaved. Some slave traders captured slaves; others purchased them from tribal chiefs, for whom the sale of slaves constituted an important source of income. “Europeans did not invent the African slave trade,” argues Dan McLaughlin; “they found it already in progress and made it their own.” Slavery in Africa started before the transatlantic slave trade and persisted after. It wasn’t outlawed in Nigeria until 1936 or in Ethiopia until 1942.

On the American continent, slavery long preceded the establishment of British settlements along the Atlantic seaboard, writes Paul Schwennesen:

Slavery was well-established in North America at least one hundred years before the alleged “beginning” of the American slavery story. Complete with the myriad complexities, contradictions and paradoxes of real life, the Spanish Americas (including much of what is today the United States) were awash in slavery. Slavery between Indians. Enslavement of Indians by Spaniards. Enslavement of Spaniards by Indians. And yes, tragically, enslavement of blacks, ladinos [i.e. mestizos], Moors, and every distinction between. It was messy, it was endemic, and it was very real—but it was certainly not confined exclusively to Blacks, nor to early Americans in Virginia.

Although not unique in tolerating slavery, the United States was unique in articulating ideals utterly incompatible with it:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

Some provisions of the Constitution implicitly acknowledged, and even protected, slavery. Rightfully embarrassed by that, the framers didn’t mention slavery by name, employing elaborate circumlocutions to avoid the term. The Father of the Constitution, James Madison, “thought it wrong to admit in the Constitution the idea that there could be property in men.”

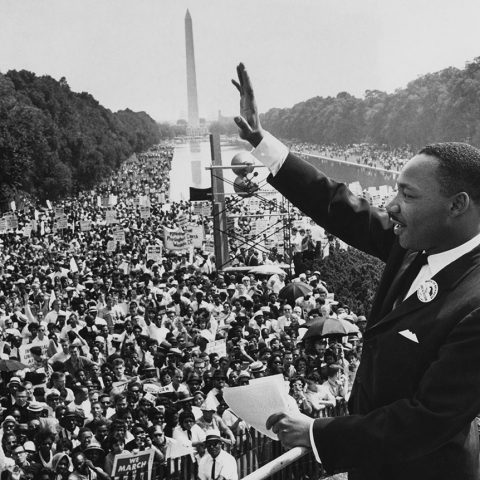

Because the Constitution originally accommodated slavery, some have condemned the founding fathers as racists and hypocrites. That’s like criticizing a Model T for not being a Tesla. The wonder is not that America took time to live up to its founding ideals; the wonder is that those ideals—bold, universal, admitting no exceptions—were promulgated in the first place. As the Reverend Martin Luther King said,

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men — yes, Black men as well as white men — would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. . . .

So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.

At its best, that’s America’s story: a continuing striving to put our creed into practice. For all our national faults and failings, past and present, it’s an exceptional story, well worth celebrating.

___

Donate Today

Supporting America’s first principles of freedom is essential to ensure future generations understand and cherish the blessings of liberty. With your donation, we will reach even more young people with the truth of America’s unique past, its promising future, and the liberty for which it stands. Help us prepare the next generation of leaders.