National Civics Day Celebrates The Federalist Papers

By David Harmer

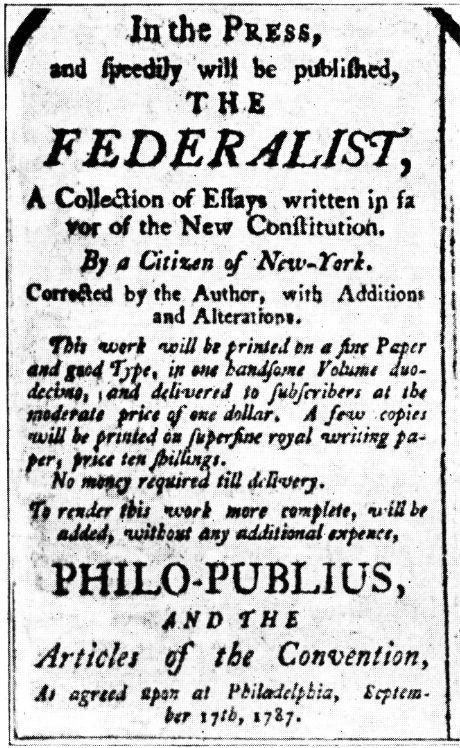

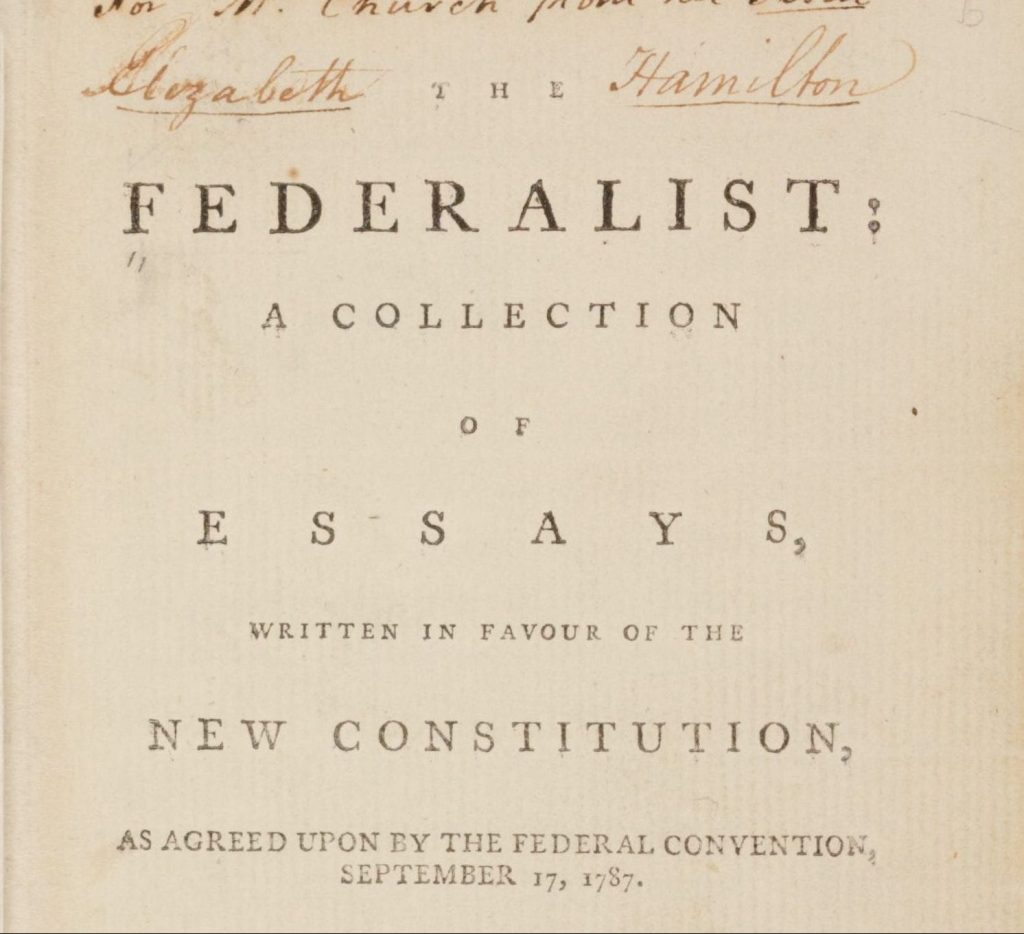

Today is National Civics Day, commemorating the publication on October 27, 1787, of the first of what would become known as The Federalist Papers. Authored variously by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison, all under the pen name Publius, these 85 brilliant and influential essays explained the proposed Constitution for the United States of America and promoted its ratification. In honor of the occasion, let’s review.

July 4, 1776: From Independence Hall, Philadelphia, the Second Continental Congress declares that the thirteen colonies are free and independent states. Bold though it is, declaring independence is the easy part; securing it requires the American Revolutionary War.

October 19, 1781: The last major military engagement of the war culminates in American victory; British General Charles Cornwallis surrenders to General George Washington at Yorktown, Virginia.

September 3, 1783: The Treaty of Paris formally ends the war; Great Britain recognizes the independence of the United States. But the states are united only in name, not in fact.

September 11-14, 1786: Commissioners from five states meet in Annapolis, Maryland, to discuss impediments to interstate commerce. Finding questions of trade inseparable from the pervasive deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation, they bemoan “the embarrassments which characterize the present State of our national affairs” and urge representatives of all states to meet the following May in Philadelphia “to take into consideration the situation of the United States [and] to devise such further provisions as shall appear to them necessary.”

September 17, 1787: The Philadelphia Convention promulgates the Constitution. Of the Convention’s objectives and outcome, James Madison writes:

Each of these objects was pregnant with difficulties. The whole of them together formed a task more difficult than can be well concieved [sic] by those who were not concerned in the execution of it. Adding to these considerations the natural diversity of human opinions on all new and complicated subjects, it is impossible to consider the degree of concord which ultimately prevailed as less than a miracle.

Miraculous it may be, but the Constitution requires ratification—and strenuous opposition has arisen. In several states, the votes for ratification are hard-fought and close: Massachusetts, 187-168; New Hampshire, 57-46; Virginia, 89-79. New York looks to be closer still; the Anti-Federalists appear to be winning the war for public opinion. In response, Hamilton, Madison, and Jay publish The Federalist Papers.

/////

In Federalist No. 1, published in The Independent Journal and addressed to the people of New York, Hamilton sets forth the stakes:

You are called upon to deliberate on a new Constitution for the United States of America. The subject speaks its own importance; [. . .] it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force. [. . .] The crisis at which we are arrived may with propriety be regarded as the era in which that decision is to be made; and a wrong election of the part we shall act may, in this view, deserve to be considered as the general misfortune of mankind.

The essays that follow address:

1. Dangers from foreign force and influence (Nos. 2-5)

2. Dissensions and hostilities between the states (Nos. 6-8)

3. Faction and insurrection (Nos. 9-10)

4. Commercial relations, revenue, and economy in government (Nos. 11-13)

5. Objections to the Constitution (Nos. 14, 38, 84)

6. Inadequacy of the Articles of Confederation (Nos. 15-22)

7. Necessity of energetic government (No. 23)

8. Defense and militia (Nos. 24-29)

9. Taxation (Nos. 30-36)

10. Proper form of government; powers of Convention (Nos. 37, 39-40)

11. Powers conferred by the Constitution; restrictions on the states (Nos. 41-46)

12. Structure of government; checks and balances (Nos. 47-51)

13. House of Representatives (Nos. 52-61)

14. Senate (Nos. 62-66)

15. Executive (Nos. 67-77)

16. Judiciary (Nos. 78-83)

In his concluding essay, Federalist No. 85, Hamilton urges readers not to make the perfect—alluring and illusory—the enemy of the satisfactory:

The system, though it may not be perfect in every part, is, upon the whole, a good one; is the best that the present views and circumstances of the country will permit; and is such an one as promises every species of security which a reasonable people can desire.

[. . .] I never expect to see a perfect work from imperfect man. The result of the deliberations of all collective bodies must necessarily be a compound, as well of the errors and prejudices, as of the good sense and wisdom, of the individuals of whom they are composed. The compacts which are to embrace thirteen distinct States in a common bond of amity and union, must as necessarily be a compromise of as many dissimilar interests and inclinations. How can perfection spring from such materials?

Thank heaven for Hamilton, Madison, and Jay! Their advocacy worked. (Barely. New York’s ratification vote was closer than that of any preceding state: 30 to 27.) And their words have endured, proving as timeless as they were timely, continuing to demonstrate the necessity and merit of our miraculous Constitution.

Donate Today

Supporting America’s first principles of freedom is essential to ensure future generations understand and cherish the blessings of liberty. With your donation, we will reach even more young people with the truth of America’s unique past, its promising future, and the liberty for which it stands. Help us prepare the next generation of leaders.